Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

Future collectible – Honda CBR1100XX Super Blackbird

by Guy ‘Guido’ Allen; pics by Honda and Ben Galli Photography

October 2020

High Flyer

Honda’s Blackbird may have been over-run in the performance stakes, but it’s still a formidable bit of kit

To this day, over two decades later, it all seems a bit mad. Motorcycle makers – or at least some of them – were locked in this power race for the bragging rights attached to having the world’s fastest production motorcycle. In 1996, for the 1997 model year, Honda snatched the gong with its CBR1100XX, aka the Super Blackbird.

It could claim a legitimate 290km/h top speed, a little

quicker than Kawasaki’s reigning ZZ-R1100. A couple of

years later, Suzuki wandered in and trounced the lot of

them with the GSX1300R Hayabusa.

Never mind the power race, there was something else going

on: the Blackbird marked a significant step in the

progression of the sophistication of big performance

motorcycles. Perhaps greater than we realised when they

were first launched.

So what was this wonderful new technology? Err, there

wasn’t any, really. It’s all about refinement and

attention to detail. This was a very conventional

sports-touring multi. The chassis was based on a big and

solid twin-spar aluminium frame, with conventional fork up

front and monoshock rear. The brakes were a bit different

and we’ll get to them later.

In the engine room, you scored a 16-valve liquid-cooled

four fed by a bank of 42mm CV carbs. Those carburettors

were replaced with the firm’s in-house injection for the

second-gen bike, in 1999. Meanwhile the transmission was a

six-speeder with an hydraulically-actuated wet clutch.

That lot added up to compelling if not revolutionary

stats: 164 horses (112kW) for a dry weight of 223. Plenty

of urge in a package that was pretty trim, given it was in

fact a reasonably civilised two-seater.

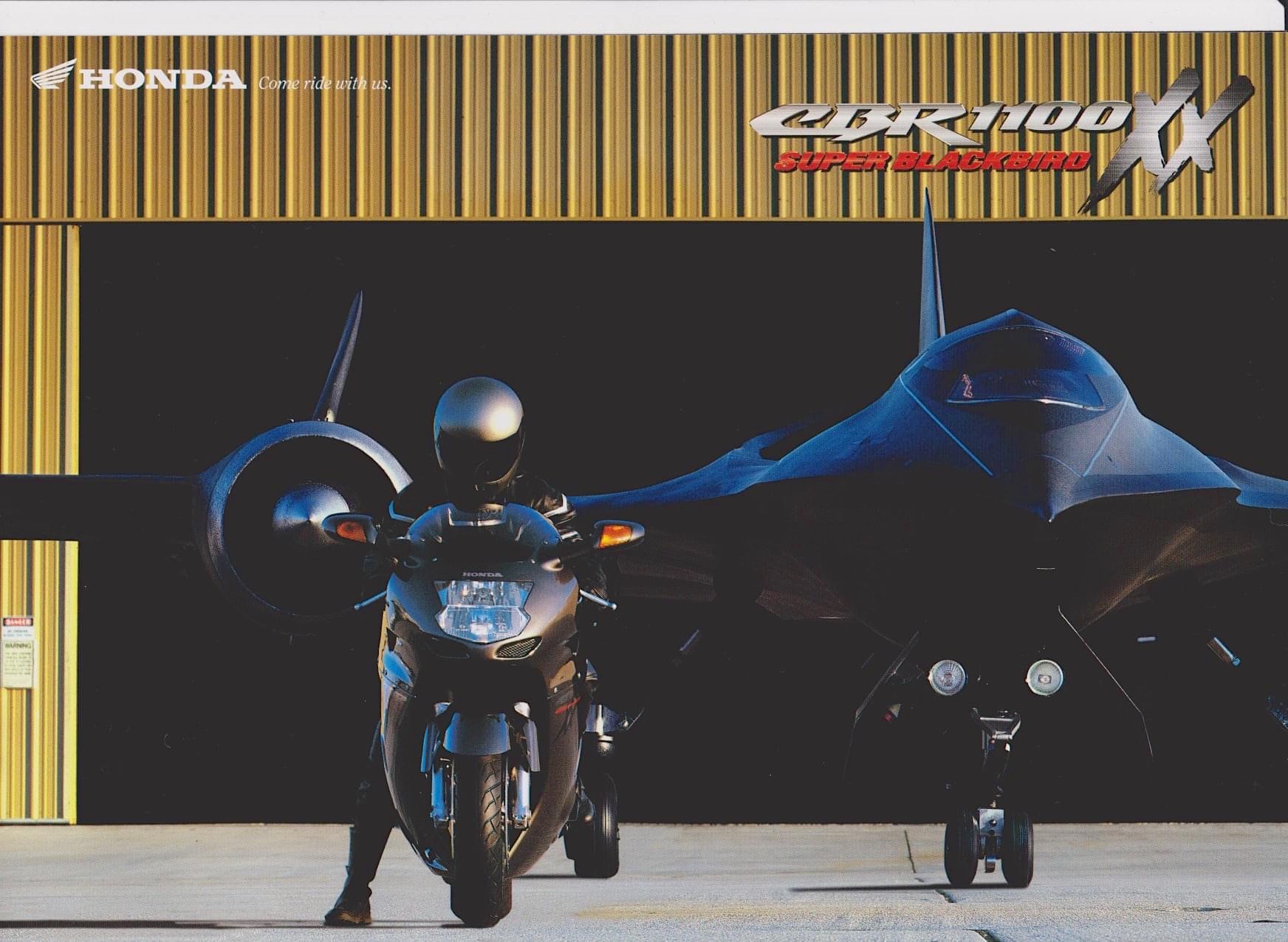

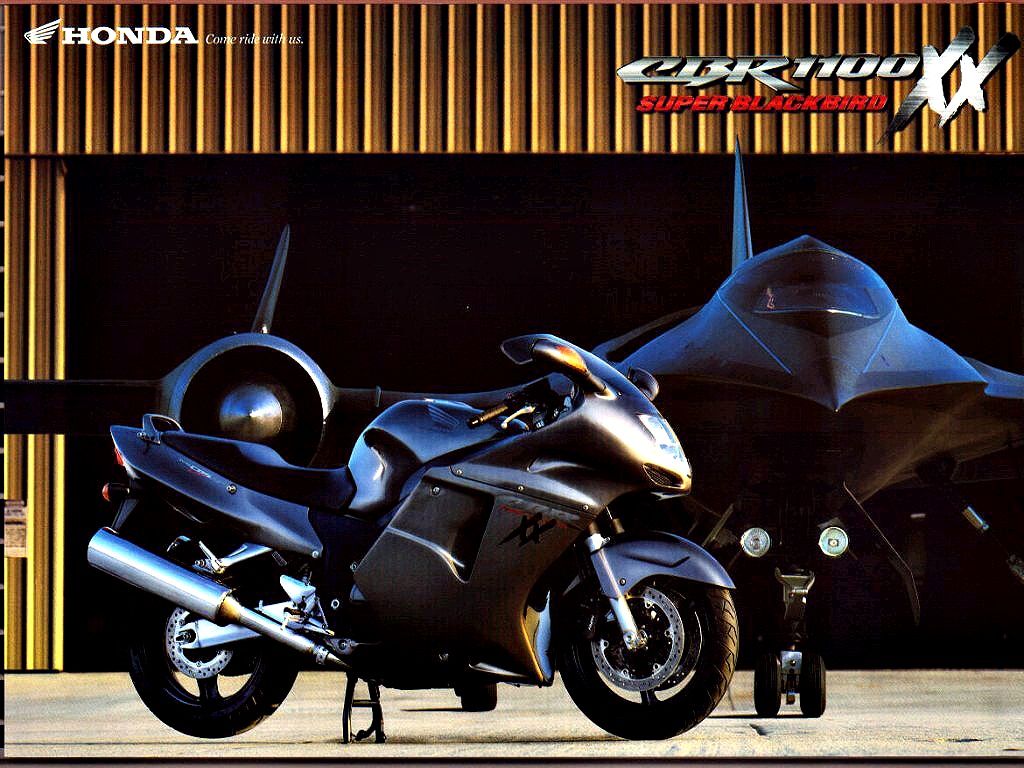

At the time, the give-away this was something a bit

special was the styling. The ‘stacked’ headlight was

definitely an out-there design cue for the day, while the

understated graphics and strangely-shaped tail were

talking points. What the…? The clue was in the name –

Blackbird. Honda’s latest flight of fancy was an homage to the

3900km/h Lockheed SR-71 spy plane and, if you look

at both, you can see the styling links – particularly in

the headlamp and tail section of the motorcycle.

What was it like in the saddle? Fast. Yeah, righto, you

could probably predict that. For its day, this was a

formidably quick bit of kit. The one criticism was a flat

spot in the mid-range in the carburettor model, which

could be tuned out to some extent. Really, I’ve not heard

owners complaining about it, and many riders will never

notice. Any hint of that disappeared on the injected

versions. With revs on board, in carburettor or injected

form, this is a fast and ultra-smooth powerplant that

seems to keep on giving right the way through to its

10,000rpm peak power point.

In fact, tied with capable suspension running very much

road rather than track rates, this is a deceptively quick

motorcycle. It’s all too easy to hop on and very soon

discover you’re travelling a whole lot quicker than

intended.

Since we’ve raised suspension, the only adjustment was for

rear spring preload and rebound damping. That was

under-done, given the performance expectations and its

status.

The rates were well thought out as a compromise and there was enough travel for this to be a comfortable travelling companion while supplying a fair degree of feedback and control. You’re unlikely to set lap records, but you can do very respectable point-to-point times. Steering was light enough for a bike this size and the accuracy pretty good.

By now, many would benefit from a suspension refresh or upgrade.

Honda’s Dual Combined Braking System (DCBS) was by far the

most controversial part of the package. It was designed

so, no matter which lever you used, you got some front and

rear retardation. What you had was three by three-piston

brake calipers operated in various combinations by both

the foot and hand brake levers, and modulated by

proportioning valves. DCBS went through some ‘tuning’

changes over its lifespan.

Its advantage was it gave the bike a very stable and flat

attitude under hard braking. Disadvantages included no

separate control over the rear for low-speed manouvering,

plus – on the MkI version - the possibility you could lock

the rear brake with the font lever, albeit under very

extreme conditions. We’re talking solo super-hard braking

on a steep downhill surface where the rear wheel was

unloaded.

The second generation Blackbird scored an updated DCBS

‘tune’ and was better for it. Really either system was

easy enough to adapt to as a rider. In the workshop, you

need to be aware that bleeding the system is a little

different to most and actually reading the maker’s

instructions is advisable.

What really sells this model, particularly as a used buy,

is the quality of design and construction. This would rate

as one of the most ‘together’ motorcycles Honda ever

produced – it feels and looks like a quality product. I

reckon this aspect is what kept a lot of people in the

Honda fold, even when Suzuki came out with a newer and

shinier toy in the shape of the Hayabusa.

Servicing is relatively light on the wallet. The intervals

for shims/valve lash are 24,000km and I would not feel any

urge to shorten them. Aside from that it’s the usual

fluids and filters. It does take patience to get into

these things, as you need to remove a fair few components

to get to the top of the engine. It’s typical for a

fully-faired multi of the period, but still a chore.

Mileage really doesn’t worry these things, so long as they

get a little love. Something with 100,000km on it should

still be a very long way from worn out, though you might

consider a camchain and tensioner check-up as a

precaution.

There were three generations: carbureted, plus two

injected. The second injected bike had a catalytic

converter, which robbed some power, and a digital/analogue

dash mix.

Despite the fact I’ve whined about DCBS over the years,

I’ve owned all three variants and now have a first model

in the shed. That, I might add, still feels like a

surprisingly competent ride.

Prices seem to vary from $3000 to $10,000, with the middle

of that range offering some red-hot value if premium

condition and bang for your buck are prime concerns. Of

the three editions, the first will long-term be the most

collectible, while the second is my pick as a ride –

ultra-well sorted, still with full power, and a

traditional analogue dash. (See What Bird is That

below.)

Could it one day be a classic? Well I reckon it will

happen. It was a landmark model for the brand and has the

huge advantage of a sexy name with a good derivation.

Late-nineties motorcycles aren’t generally on the radar of

collectors just yet, but they will get there. In the

meantime you’d have something that is a truly good ride.

***

See a story on rejetting our own Blackbird, here

See our 2013 video review of this bike (above)

ONLINE OWNER GROUPS

International: cbrxx.com

and cbr1100xx.org

***

Blackbird’s Dad

Honda’s project leader on the Blackbird, Isao Yamanaka,

holidayed in Australia back in 2000 and took a little time

out to chat with a gaggle of bike journos. He turned out

to be a true bike nut with a fascinating background.

His career, which started with Honda in 1974, included

working on the teams for the Honda Bol d’Or series, the

notorious NR500/750 eight-valve project and numerous

others.

And his prime interests away from work? Football and beer…

What Bird is That?

Blackbirds were built from 1996 (for the 1997 model year)

through to 2007. There were three generations:

1997-1998: Carburettors, 22 litre fuel tank, 164hp

claimed;

1999-2000: Injected, 24 litre fuel tank, two-deck

tail-light, 164hp claimed;

2000-2007: Mixed analogue/digital dash, catalytic

converter, 152hp claimed.

Several other running changes were made, for example a new

front hub and discs between gen 1 and 2, plus alterations

to the set-up of the linked brake system across all three

generations.

Blackbird vs Hayabusa vs ZX-12R

It seems to be one of those rules in life that

you can’t publish anything online about Blackbirds without

someone assuring you a 'Busa or a Kawasaki ZX-12R is

better. Well, yes and no.

Suzuki’s first-gen Hayabusa claimed more power (175 vs

164hp) and a little more torque lower down the rev range

(126Nm @ 6250rpm vs 124Nm @ 7250rpm). Equally significant

from a performance point of view was the claim for

superior aerodynamics and its accompanying dramatic

styling. In the end that meant a top speed of just over

300km/h versus 290.

Then came Kawasaki with the

ZX-12R Ninja, which claimed more like 189 horses,

and was speed-limited to 299kph (180mph).

As someone who owns all three models, I can tell you the

Blackbird is actually a more refined ride and probably the

pick for long trips. It’s smoother and just that little

bit better integrated. It also has linked brakes, which

may or may not be a benefit, depending on your point of

view.

The Hayabusa is a thoroughly entertaining brute with a

surprising level of civility when ridden gently, while the

Kawasaki is a very quick bit of kit with a little more

sporting potential.

So which one is better? It depends on what you’re looking

for…

See our first-gen Suzuki Hayabusa buyer guide here

See the Classic Two Wheels 1999 Haybusa road test here

SPECS:

Honda CBR1100XX Blackbird (1997-2007)

ENGINE:

TYPE: Liquid-cooled, four-valves-per-cylinder, inline four

CAPACITY: 1137cc

BORE & STROKE: 79 x 58mm

COMPRESSION RATIO: 11:1

FUEL SYSTEM: 42mm Keihin CV carbs or Honda fuel injection

TRANSMISSION:

TYPE: Six-speed, constant-mesh,

FINAL DRIVE: Chain

CHASSIS & RUNNING GEAR:

FRAME TYPE: Aluminium twin-spar

FRONT SUSPENSION: Cartridge telescopic fork, 120mm travel

REAR SUSPENSION: Preload-adjustable & rebound

dampingvs adjustable monoshock, 120mm travel

FRONT BRAKE: 310mm discs with three-piston calipers DCBS

REAR BRAKE: 256mm disc with three-piston caliper DCBS

DIMENSIONS & CAPACITIES:

DRY/WET WEIGHT: 223/254kg

SEAT HEIGHT: 810mm

WHEELBASE: 1490mm

FUEL CAPACITY: 22 or 24lt

WHEELS & TYRES:

FRONT: 3-spoke cast alloy , 120/70 ZR17

REAR: 3-spoke cast alloy, 180/55 ZR17

PERFORMANCE:

POWER: 122kW @ 10,000rpm (113kW in third edition with Cat)

TORQUE: 124Nm @ 7250rpm

OTHER STUFF:

PRICE WHEN NEW: $16500-18,790 + ORC

Good:

Fast

Comfortable

Well made

Not so good:

Not ideal as a track bike

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact